Thanksgiving

De Mi caja de notas

| Día de Acción de Gracias | ||

|---|---|---|

Familia dando las gracias a Dios antes de cortar el pavo en una cena de Acción de Gracias en el estado de Pensilvania (Estados Unidos), 1942. | ||

| Localización | ||

| Localidad | Estados Unidos, Canadá, Liberia, Santa Lucía, Isla Norfolk y Brasil | |

| Coordenadas | 39°49′41″N 98°34′46″O / 39.828175, -98.5795 | |

| Datos generales | ||

| Tipo | Festivos federales en Estados Unidos y Canadá | |

| Fecha |

Segundo lunes de octubre (Canadá) Cuarto jueves de noviembre (Estados Unidos y Brasil) Primer jueves de noviembre (Liberia) | |

El Día de Acción de Gracias (en inglés: Thanksgiving Day) es una fiesta celebrada oficialmente en Estados Unidos y Canadá, así como en Granada, Santa Lucía, y Liberia, y de forma no oficial por comunidades de inmigrantes estadounidenses y canadienses en México, Australia, Filipinas, Israel y Centroamérica.

Originalmente, fue un día de agradecimiento por la cosecha y por el año anterior. En Alemania, Suiza y Japón se conmemoran festividades similares de fin de año. El Día de Acción de Gracias se celebra el cuarto jueves de noviembre en los Estados Unidos, y el segundo lunes de octubre en Canadá. Aunque el Día de Acción de Gracias tiene raíces históricas en las tradiciones religiosas y culturales.[1][2]

Historia

Las oraciones de agradecimiento y las ceremonias especiales de Acción de Gracias son comunes entre casi todas las culturas después de las cosechas y en otras ocasiones. Su historia en América del Norte tienen como origen, las tradiciones norteamericanas que datan de la reforma protestante. También tiene aspectos de un festival de la cosecha, a pesar de que la cosecha en Nueva Inglaterra ocurre mucho antes del final de noviembre, fecha en la que se celebra el Día de Acción de Gracias. En la tradición inglesa, los días de Acción de Gracias y los servicios especiales de agradecimiento religiosos a Dios, se hicieron importantes durante la reforma anglicana, en el reinado de Enrique VIII y en reacción al gran número de festividades religiosas del calendario católico. Antes de 1536, había 95 días festivos de la iglesia, más 52 domingos, en los cuales las personas debían asistir a la iglesia y renunciar al trabajo, y a veces pagar costosas celebraciones. Las reformas de 1536 redujeron el número de festividades de la Iglesia a 27, pero algunos puritanos deseaban eliminar por completo todas las festividades de la iglesia, incluyendo la Navidad y la Pascua.

Los días festivos serían reemplazados por días especialmente llamados de ayuno o días de acción de gracias, en respuesta a eventos que los puritanos consideraban como actos de divina providencia. Los desastres inesperados o las amenazas de un juicio divino exigían días de ayuno. Las bendiciones especiales, vistas como provenientes de Dios, requerían de días de dar gracias. Por ejemplo, los días de ayuno fueron llamados así por la sequía en 1611, las inundaciones en 1613 y las plagas de 1604 y 1622. Los días de dar gracias fueron llamados así después de la victoria sobre la armada española en 1588 y después de la liberación de la reina Ana en 1705. Un inusual día de acción de gracias anual comenzó en 1606, después del fracaso de la conspiración de la pólvora en 1605, y que se convirtió en la noche de Guy Fawkes (5 de noviembre).[3]

En Canadá

Durante su último viaje a estas regiones en 1609, Frobisher llevó a cabo una ceremonia formal en la actual bahía de Frobisher, isla de Baffin (actualmente Nunavut) para dar las gracias a Dios; más tarde, celebraron la comunión en un servicio llevado a cabo por el ministro Robert Wolfall, el primer servicio religioso de ese tipo en la región.[4] Años después, la tradición de la fiesta continuó a medida que fueron llegando más habitantes a las colonias en Canadá.[5]

Los orígenes del día de Acción de Gracias en Canadá también pueden remontarse a principios del siglo XVII, cuando los franceses llegaron a Nueva Francia con el explorador Samuel de Champlain y celebraron sus cosechas exitosas. Los franceses de la zona solían tener fiestas al final de la temporada de cosechas y continuaban celebrando durante el invierno, e incluso compartían sus alimentos con los nativos de la región.[6]

A medida que fueron llegando más inmigrantes europeos a Canadá, las celebraciones después de una buena cosecha se fueron volviendo tradición. Los irlandeses, escoceses y alemanes también añadirían sus costumbres a las fiestas. La mayoría de las costumbres estadounidenses relacionadas con el día de Acción de Gracias (como el pavo o las gallinas de Guinea, provenientes de Madagascar), se incorporaron cuando los lealistas comenzaron a escapar de los Estados Unidos durante la Revolución de las Trece Colonias y se establecieron en Canadá.

En Estados Unidos

En los Estados Unidos, la tradición moderna del día de Acción de Gracias tiene sus orígenes en el año 1621 en una celebración en Plymouth, en el actual estado de Massachusetts. También existen evidencias de que los colonos ingleses en Texas realizaron celebraciones en el continente con anterioridad en 1598, y fiestas de agradecimiento en la colonia de Virginia.[7] La fiesta en 1621 se celebró en agradecimiento por una buena cosecha. En los años posteriores, la tradición continuó con los líderes civiles tales como el gobernador William Bradford, quien planeó celebrar el día y ayudar en 1623.[8][9][10] Dado que al principio la colonia de Plymouth no tenía suficiente comida para alimentar a la mitad de los 102 colonos, los nativos de la tribu Wampanoag ayudaron a los peregrinos dándoles semillas y enseñándoles a pescar. La práctica de llevar a cabo un festival de la cosecha como este no se volvió una tradición habitual en Nueva Inglaterra hasta finales de la década de 1660.[11]

Según el historiador Jeremy Bangs, director del Leiden American Pilgrim Museum, los peregrinos pudieron haberse inspirado en los servicios anuales de Acción de Gracias por el alivio del asedio de Leiden en 1574, cuando vivían en Leiden.[12]

Controversia sobre el origen

El sitio donde se llevó a cabo el primer día de Acción de Gracias en los Estados Unidos, e incluso en el continente, es un objeto de debate constante. Los escritores y profesores Robyn Gioia y Michael Gannon de la Universidad de la Florida han señalado que la primera celebración de este día en lo que actualmente son los Estados Unidos fue llevada a cabo por los colonos españoles el 8 de septiembre de 1565, en lo que hoy es San Agustín, Florida.[13][14]

En Liberia

En Liberia, país de África occidental, el Día de Acción de Gracias se celebra el primer jueves de noviembre.[15] En 1883, la Legislatura de Liberia promulgó un estatuto declarando este día como feriado nacional.[16] El Día de Acción de Gracias se celebra en el país en gran parte debido a la fundación de la nación como colonia de la estadounidense en 1821. Sin embargo, la celebración liberiana de la festividad es notablemente diferente de la celebración estadounidense. Si bien algunas familias liberianas optaron por celebrar con un banquete o cocinar al aire libre, no se considera un elemento básico de la festividad y no existe ningún alimento específico fuertemente asociado con el Día de Acción de Gracias. En los años posteriores a la segunda guerra civil, algunos liberianos han tomado la celebración como un momento para agradecer este nuevo período de paz y relativa estabilidad, dando un nuevo significado a la celebración.[15]

En Brasil

En Brasil, el entonces presidente Gaspar Dutra instituyó el Día Nacional de Acción de Gracias, a través de la ley 781, del 17 de agosto de 1949, por sugerencia del embajador Joaquim Nabuco. En 1966, la ley 5110 estableció que la celebración de Acción de Gracias se daría el cuarto jueves de noviembre.[17] Pero esta celebración no es muy popular.

Tradiciones en los Estados Unidos

Cenas familiares

La mayoría de las personas en los Estados Unidos celebran esta fiesta con reuniones familiares en sus hogares donde preparan un banquete, en muchas casas es común ofrecer una oración de gracias a Dios por las bendiciones recibidas durante el año. El plato principal tradicional para la cena es un gran pavo asado u horneado, este pavo tradicionalmente va acompañado con un relleno hecho de pan de maíz y salvia. Se sirve tradicionalmente con una jalea o salsa de arándanos rojos, además suelen servirse platos de verduras como las judías verdes, la papa dulce (boniato, camote) y el puré de patata con gravy, que es una salsa hecha del jugo del pavo; también suele servirse una gran variedad de postres, siendo el pastel de calabaza el más popular. Las comidas se sirven con sidra de manzana caliente con especias (spiced hot apple cider) o espumoso de sidra de manzana, tradicionalmente fermentado (sparkling apple cider o hard cider).[18][19] También es común preparar el pastel de nuez pacana y el de manzana.

Desfile en Manhattan

Anualmente la cadena de tiendas departamentales Macy's realiza un gran desfile por las calles de Manhattan, Nueva York, que atrae a millones de personas a la avenida Broadway para ver los enormes globos gigantes y presenciar las actuaciones de artistas musicales invitados, turistas y habitantes locales de la ciudad, disfrutan del desfile financiado por el Municipio y empresas privadas.

Inicio de la temporada de compras

La mayoría de negocios y oficinas están cerrados en este día. Algunos almacenes, centros comerciales, restaurantes y bares permanecen abiertos. El viernes siguiente a la fiesta es tradicional la apertura de la temporada de compras navideñas. Este día se conoce como «viernes negro». Almacenes y tiendas todos ofrecen precios de rebaja y mucha gente acude desde las primeras horas del día a los centros comerciales.

Véase también

Referencias

- ↑ Silverman, David J. (25 de noviembre de 2020). «Thanksgiving Day» (en inglés). Consultado el 28 de noviembre de 2020. «Los estadounidenses generalmente creen que su Acción de Gracias se basa en una fiesta de la cosecha de 1621 compartida por los colonos ingleses (Peregrinos) de Plymouth y el pueblo Wampanoag».

- ↑ Instituto de Información Jurídica, Universidad Cornell. «5 Código de EE. UU. § 6103. Días festivos» (en inglés). Consultado el 28 de noviembre de 2020. «Día de Acción de Gracias, cuarto jueves de noviembre».

- ↑ Baker, James W. (2009). Thanksgiving: the biography of an American holiday. UPNE. pp. 1-14. ISBN 9781584658016.

- ↑ «The three voyages of Martin Frobisher: in search of a passage to Cathai and India by the northwest AD 1576-1578».

- ↑ Morill, Ann Thanksgiving and Other Harvest Festivals Infobase Publishing, ISBN 1-60413-096-2 p.31

- ↑ Solski, Ruth Canada's Traditions and Celebrations McGill-Queen's Press, ISBN 1-55035-694-1 p.12

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan. 2011. Thanksgiving. Eds. Cutler Cleveland & Peter Saundry. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC

- ↑ Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647, pp. 120-121.

- ↑ Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, pp. 135-142.

- ↑ The fast and thanksgiving days of New England by William DeLoss Love, Houghton, Mifflin and Co., Cambridge, 1895

- ↑ Kaufman, Jason Andrew The origins of Canadian and American political differences Harvard_University_Press, 2009, ISBN 0-674-03136-9 p.28

- ↑ Jeremy Bangs. «Influences». The Pilgrims' Leiden. Archivado desde el original el 13 de enero de 2012. Consultado el 23 de noviembre de 2011.

- ↑ Wilson, Craig (21 de noviembre de 2007). «Florida teacher chips away at Plymouth Rock Thanksgiving myth». Usatoday.com. Consultado el 23 de noviembre de 2011.

- ↑ Davis, Kenneth C. (25 de noviembre de 2008). «A French Connection». Nytimes.com. Consultado el 23 de noviembre de 2011.

- ↑ a b «Vice President Boakai Joins Catholic Community in Bomi to Celebrate Thanksgiving Day». web.archive.org. 6 de octubre de 2014. Archivado desde el original el 6 de octubre de 2014. Consultado el 2 de noviembre de 2023.

- ↑ «Ellen declares Thursday, 2 November as National Thanksgiving Day». Liberia news The New Dawn Liberia, premier resource for latest news (en inglés estadounidense). 1 de noviembre de 2017. Consultado el 2 de noviembre de 2023.

- ↑ «Dia Nacional de Ações de Graças». Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública (en portugués de Brasil). Consultado el 2 de noviembre de 2023.

- ↑ TheKitchn.com - Thanksgiving Refreshment: What about Hard Cider?, Bebida de Acción de Gracias (en inglés) - Consultado el 2013-12-26

- ↑ MarthaStewart.com Archivado el 5 de diciembre de 2014 en Wayback Machine. 15-delicious-cider-recipes, 15 deliciosas recetas con sidra (en inglés) - Consultado el 2013-12-26

Enlaces externos

Wikimedia Commons alberga una categoría multimedia sobre Día de Acción de Gracias.

Wikimedia Commons alberga una categoría multimedia sobre Día de Acción de Gracias.

| Thanksgiving | |

|---|---|

Thanksgiving at Plymouth, oil on canvas, by Jennie Augusta Brownscombe, 1925 | |

| Observed by | United States |

| Type | National |

| Celebrations | Giving thanks, prayer, feasting, football games, spending time with family, religious services, parades[1][a] |

| Date | Fourth Thursday in November |

| 2025 date | November 27 |

| 2026 date | November 26 |

| 2027 date | November 25 |

| 2028 date | November 23 |

| Duration | one day |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | |

Thanksgiving is a federal holiday in the United States celebrated on the fourth Thursday of November (which became the uniform date country-wide in 1941). The earliest Thanksgiving can occur is November 22; the latest is November 28.[2][3] Outside the United States, it is called American Thanksgiving to distinguish it from the Canadian holiday of the same name and related celebrations in other regions. As the name implies, the holiday generally revolves around giving thanks and the centerpiece of most celebrations is a Thanksgiving dinner with family and friends.[4][5]

The modern national celebration dates to 1863; prior to this, it was a regional holiday, whose origins lie in the 17th and 18th century days of thanksgiving of Calvinist New England. The evolution of the holiday was not linear (various New England communities had independently developed their own similar traditions that slowly turned into a singular annual Thanksgiving Day); the first known civil day of thanksgiving in the New England tradition was declared at Plymouth Colony in 1623,[6] two years after the famous 1621 harvest celebration popularized as the "first Thanksgiving" bearing a substantial, if a coincidental, similarity to what Thanksgiving Day would eventually become.[7] Celebrations of Thanksgiving for the harvest in New England became a regular occurrence by the 1660s.[8]

Thanksgiving dinner often consists of foods associated with New England harvest celebrations: turkey, potatoes (usually mashed and sweet), squash, corn (maize), green beans, cranberries (typically as cranberry sauce), and pumpkin pie. It has expanded over the years to include specialties from other regions of the United States, such as macaroni and cheese and pecan pie in the South and wild rice stuffing in the Great Lakes region, as well as international and ethnic dishes.

Other Thanksgiving customs include charitable organizations offering Thanksgiving dinner for the poor, attending religious services, and watching or participating in parades and American football games. Thanksgiving is also typically regarded as the beginning of the holiday shopping season, with the day after, Black Friday, often considered to be the busiest retail shopping day of the year in the United States. Cyber Monday, the online equivalent, is held on the Monday following Thanksgiving.

History

Days of thanksgiving

Days of thanksgiving, days attributed to giving thanks to deities, have existed for thousands of years and long predate the European colonization of North America. The first recorded "Thanksgiving" in North America occurred in 1578 in Nunavut, held by Sir Martin Frobisher and his crew.[9][10]

Documented thanksgiving services in what is currently the United States were conducted as early as the 16th century by the Spaniards[11][12][13]

and the French.[14] These days of thanksgiving were celebrated through church services and feasting.[4] Historian Michael Gannon claimed St. Augustine, Florida, was founded with a shared thanksgiving meal on September 8, 1565.[15] The thanksgiving at St. Augustine was celebrated 56 years before the Puritan Pilgrim thanksgiving at Plymouth Colony (in what is now Massachusetts), but it did not become the origin of the national annual tradition.[16]

Thanksgiving services were routine in what became the Commonwealth of Virginia as early as 1607;[17] the first permanent settlement of Jamestown, Virginia, held a thanksgiving in 1610.[11] On December 4, 1619, 38 English settlers celebrated a thanksgiving immediately upon landing at Berkeley Hundred, Charles City. The group's London Company charter specifically required "that the day of our ships arrival at the place assigned for plantation in the land of Virginia shall be yearly and perpetually kept holy as a day of thanksgiving to Almighty God".[18][19] This celebration has, since the mid 20th century, been commemorated there annually at present-day Berkeley Plantation, the ancestral home of the Harrison family of Virginia.[20][21]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

Harvest festival observed by the Pilgrims at Plymouth

The Plymouth colonists, today known as Pilgrims,[23] had settled in a part of eastern Massachusetts formerly occupied by the Patuxet Indians who had died in a devastating epidemic between 1614 and 1620. After the harsh winter of 1620–1621 killed half of the Plymouth colonists, two Native intermediaries, Samoset and Tisquantum (more commonly known by the diminutive variant Squanto, and the last living member of the Patuxet) came in at the request of Massasoit, leader of the Wampanoag, to negotiate a peace treaty and establish trade relations with the colonists, as both men had some knowledge of English from previous interactions with Europeans, through both trade (Samoset) and a period of enslavement (Squanto).

Massasoit had hoped to establish a mutual protection alliance between the Wampanoag, themselves greatly weakened by the same plague that extirpated the Patuxet, and the better-armed English in their long-running rivalry with the Narragansett, who had largely been spared from the epidemic; the Wampanoag reasoned that, given that the Pilgrims had brought women and children, they had not arrived to wage war against them.

Squanto taught the Pilgrims how to catch eel and grow corn and served as an interpreter for them until he too succumbed to disease a year later. The Wampanoag leader Massasoit also gave food to the colonists when supplies brought from England proved insufficient.[24]

Having brought in a good harvest, the Pilgrims celebrated at Plymouth for three days in the autumn of 1621. The exact time is unknown, but James Baker, a former Plimoth Plantation vice president of research, stated in 1996, "The event occurred between Sept. 21 and Nov. 11, 1621, with the most likely time being around Michaelmas (Sept. 29), the traditional time."[25] Seventeenth-century accounts do not identify this as a day of thanksgiving but rather as a harvest celebration.[25]

The Pilgrim feast was cooked by the four adult Pilgrim women who survived their first winter in the New World (Eleanor Billington, Elizabeth Hopkins, Mary Brewster, and Susanna White), along with young daughters and male and female servants.[25][26][27]

According to accounts by Wampanoag descendants, the harvest feast was originally set up for the Pilgrims alone (contrary to the common misconception that the Wampanoag were invited for their help in teaching the pilgrims their agricultural techniques).[28] Part of the harvest celebration involved a demonstration of arms by the colonists, and the Wampanoag, having entered into a mutual protection agreement with the colonists and likely mistaking the celebratory gunfire for an attack by a common enemy, arrived fully armed. The Wampanoag were welcomed to join the celebration, as their farming and hunting techniques had produced much of the bounty for the Pilgrims, and contributed their own foods to the meal.[29][30][24]

Most modern imaginings of the celebration promote the idea that every party involved ate solely turkey.[31] However, "while the celebrants might well have feasted on wild turkey, the local diet also included fish, eels, shellfish, and a Wampanoag dish called nasaump, which the Pilgrims had adopted: boiled cornmeal mixed with vegetables and meats. There were no potatoes (an indigenous South American food not yet introduced into the global food system) and no pies (because there was no butter, wheat flour, or sugar)."[32]

Two colonists gave personal accounts of the 1621 feast in Plymouth. William Bradford, in Of Plymouth Plantation, wrote:

They began now to gather in the small harvest they had, and to fit up their houses and dwellings against winter, being all well recovered in health and strength and had all things in good plenty. For as some were thus employed in affairs abroad, others were exercised in fishing, about cod and bass and other fish, of which they took good store, of which every family had their portion. All the summer there was no want; and now began to come in store of fowl, as winter approached, of which this place did abound when they can be used (but afterward decreased by degrees). And besides waterfowl, there was a great store of wild turkeys, of which they took many, besides venison, etc. Besides, they had about a peck a meal a week to a person, or now since harvest, Indian corn to the proportion. Which made many afterward write so largely of their plenty here to their friends in England, which were not feigned but true reports.[33]

Edward Winslow, in Mourt's Relation wrote:

Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruits of our labor. They four in one day killed as much fowl as, with a little help beside, served the company almost a week. At which time, amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which we brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain and others. And although it be not always so plentiful as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want that we often wish you, partakers of our plenty.[34]

New England Thanksgivings

Baker's "New England Thanksgiving" does not refer to an annual commemoration of the Pilgrims' 1621 harvest celebration. In fact, that event had largely been forgotten for over a century. Bradford's "Of Plymouth Plantation" was not published until the 1850s and the booklet "Mourt's Relation" was typically summarized by other publications without the now-familiar thanksgiving story. By the eighteenth century, the original booklet appeared to be lost or forgotten although a copy was later rediscovered in Philadelphia in 1820, with the first full reprinting in 1841. In that reprinting, in a footnote, the editor, Alexander Young, was the first person to describe the 1621 feast as the "first Thanksgiving", but this was only because he viewed it as similar to the traditions of New England Thanksgivings that had developed independently from it over the previous two hundred years.[7]

Those traditions, and the modern holiday, were born out of the gradual homogenization and, to a degree, secularization, of multiple, separate but related days of thanksgiving throughout New England. These days were often celebrated from early November to early to mid-December, in some cases functioning almost as a Calvinist alternative to Christmas, and typically involving a return to the family home, church services, a large meal and various diversions ranging from games and sports to formal balls. These celebrations were gradually disseminated throughout the US as New Englanders spread across the country, accelerating after the Civil War.[36]

Sarah Hale and Godey's Lady's Book

Sarah Josepha Hale, a native of New Hampshire and steeped in the traditions of a New England Thanksgiving, was the longtime editor of Godey's Lady's Book, the most widely circulated periodical in the antebellum U.S.[citation needed] Hale was the chief promoter of the modern idea of the holiday in the 19th century, from the foods served to the decorations to the role of women in putting it all together. Concerned by increasing factionalism in American society, Hale envisioned Thanksgiving as a commonly-celebrated, patriotic holiday that would unite Americans in purpose and values. She viewed those values as rooted in domesticity and rural simplicity over urban sophistication. As a celebration of hearth and home, she also sought to cement a role for women within the identity of the young nation.

Every November, Hale would focus her monthly magazine column on Thanksgiving, positioning the celebration as a pious, patriotic holiday that lived on in the memory as a check against temptation, or as a comfort in times of trial. Hale and Godey's led the way in creating a standardized celebration, which in turn created a standardized celebrant — a standardized and true American.

Her vision aimed at a broad audience: the stories in Godey's depicted Black servants, Roman Catholics, and Southerners celebrating Thanksgiving, and becoming more American (which for Hale meant becoming more like White Protestant Northerners) by doing so.[37]

Her efforts sought to expand the holiday from a regional celebration to a national one not only through advocacy in her magazine but also in direct appeals to several U.S. presidents, including Abraham Lincoln, who began annual national proclamations of autumn Thanksgivings in 1863.

Enter the Pilgrims

While the Pilgrims' story did not itself create the modern Thanksgiving holiday, it did become inextricably linked with it in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This was largely due to the introduction in U.S. schools of "an annual sequence of classroom holiday activities through which civic education and American patriotism were indoctrinated."[36]

The late 19th and early 20th century were a time of massive immigration to the U.S. The changing demographics prompted not only xenophobic responses in the form of restrictive immigration measures, but also a greater push towards the Americanization of newcomers and the conscious formulation of a shared cultural heritage. Holiday observances in classrooms, including those for Washington's birthday, Memorial Day, and Flag Day "introduced youngsters to the central themes of American History and, in theory, strengthened their character and prepared them to become loyal citizens." Thanksgiving, with its non-denominational character, colonial harvest themes and images of Pilgrims and Indians breaking bread together peacefully, allowed the country to tell a story of its origins—people leaving far off lands, struggling under harsh conditions and ultimately being welcomed to America's bounty—that children, particularly immigrant children, could easily understand and share with their families.[38]

The holiday materials were often disseminated in the form of booklets containing poetry and songs and crafts. Thanksgiving pageants at schools often involved a recreation of the imagined "First Thanksgiving" to reinforce the Pilgrim narrative and the importance of the story to an understanding of U.S. history. These pageants continue in some parts of the U.S. today.

Debate over the "first Thanksgiving"

Dr Jeremy Bangs opines that "local boosters in Virginia, Florida, and Texas promote their own colonists, who (like many people getting off a boat) gave thanks for setting foot again on dry land".[39]

The codification and celebration of an annual day of thanksgiving according to the Berkeley Hundred charter in Virginia prompted President John F. Kennedy to acknowledge the claims of both Massachusetts and Virginia to America's earliest celebrations. He issued Proclamation 3560 on November 5, 1963, saying: "Over three centuries ago, our forefathers in Virginia and in Massachusetts, far from home in a lonely wilderness, set aside a time of thanksgiving. On the appointed day, they gave reverent thanks for their safety, for the health of their children, for the fertility of their fields, for the love which bound them together and for the faith which united them with their God."[40]

However, according to historian James Baker, debates over where any "first Thanksgiving" took place on modern American territory are a "tempest in a beanpot".[7] According to Baker, "the American holiday's true origin was the New England Thanksgiving. Never coupled with a Sabbath meeting, the Pilgrim observances were special days set aside during the week for thanksgiving and praise in response to God's providence."[7]

Thanksgiving proclamations in the early United States

The Revolutionary War Era to the Civil War

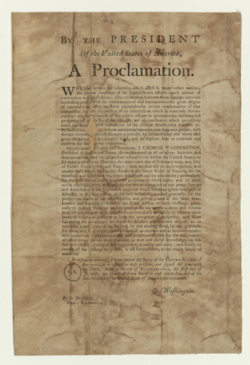

The First National Proclamation of Thanksgiving was given by the Continental Congress in 1777 from its temporary location in York, Pennsylvania, while the British occupied the national capital at Philadelphia.[41][42] Delegate Samuel Adams created the first draft. Congress then adopted the final version:

For as much as it is the indispensable Duty of all Men to adore the superintending Providence of Almighty God; to acknowledge with Gratitude their Obligation to him for Benefits received, and to implore such farther Blessings as they stand in Need of: And it had pleased him in his abundant Mercy, not only to continue to us the innumerable Bounties of his common Providence; but also to smile upon us in the Prosecution of a just and necessary war, for the Defense and Establishment of our unalienable Rights and Liberties; particularly in that he hath been pleased, in so great a Measure, to prosper the Means used for the Support of our Troops, and to crown our Arms with most signal success:

It is therefore recommended to the legislative or executive Powers of these United States to set apart Thursday, the eighteenth Day of December next, for Solemn Thanksgiving and Praise: That at one Time and with one Voice, the good People may express the grateful Feelings of their Hearts, and consecrate themselves to the Service of their Divine Benefactor; and that, together with their sincere Acknowledgments and Offerings, they may join the penitent Confession of their manifold Sins, whereby they had forfeited every Favor; and their humble and earnest Supplication that it may please God through the Merits of Jesus Christ, mercifully to forgive and blot them out of Remembrance; That it may please him graciously to afford his Blessing on the Governments of these States respectively, and prosper the public Council of the whole: To inspire our Commanders, both by Land and Sea, and all under them, with that Wisdom and Fortitude which may render them fit Instruments, under the Providence of Almighty God, to secure for these United States, the greatest of all human Blessings, Independence and Peace: That it may please him, to prosper the Trade and Manufactures of the People, and the Labor of the Husbandman, that our Land may yield its Increase: To take Schools and Seminaries of Education, so necessary for cultivating the Principles of true Liberty, Virtue and Piety, under his nurturing Hand; and to prosper the Means of Religion, for the promotion and enlargement of that Kingdom, which consisteth "in Righteousness, Peace and Joy in the Holy Ghost.

And it is further recommended, That servile Labor, and such Recreation, as, though at other Times innocent, may be unbecoming the Purpose of this Appointment, be omitted on so solemn an Occasion.[43]

George Washington, leader of the revolutionary forces in the American Revolutionary War, proclaimed a Thanksgiving in December 1777 as a victory celebration honoring the defeat of the British at Saratoga.[44]

The Continental Congress, the legislative body that governed the United States from 1774 to 1789, issued several "national days of prayer, humiliation, and thanksgiving",[45] a practice that was continued by presidents Washington and Adams under the Constitution, and has manifested itself in the established American observances of Thanksgiving and the National Day of Prayer today.[46]

This proclamation was published in The Independent Gazetteer, or the Chronicle of Freedom, on November 5, 1782, the first being observed on November 28, 1782:

By the United States in Congress assembled, PROCLAMATION.

It being the indispensable duty of all nations, not only to offer up their supplications to Almighty God, the giver of all good, for His gracious assistance in a time of distress, but also in a solemn and public manner, to give Him praise for His goodness in general, and especially for great and signal interpositions of His Providence in their behalf; therefore, the United States in Congress assembled, taking into their consideration the many instances of Divine goodness to these States in the course of the important conflict, in which they have been so long engaged; the present happy and promising state of public affairs, and the events of the war in the course of the year now drawing to a close; particularly the harmony of the public Councils which is so necessary to the success of the public cause; the perfect union and good understanding which has hitherto subsisted between them and their allies, notwithstanding the artful and unwearied attempts of the common enemy to divide them; the success of the arms of the United States and those of their allies; and the acknowledgment of their Independence by another European power, whose friendship and commerce must be of great and lasting advantage to these States; Do hereby recommend it to the inhabitants of these States in general, to observe and request the several states to interpose their authority, in appointing and commanding the observation of THURSDAY the TWENTY-EIGHTH DAY OF NOVEMBER next as a day of SOLEMN THANKSGIVING to GOD for all His mercies; and they do further recommend to all ranks to testify their gratitude to God for His goodness by a cheerful obedience to His laws and by promoting, each in his station, and by his influence, the practice of true and undefiled religion, which is the great foundation of public prosperity and national happiness.

Done in Congress at Philadelphia, the eleventh day of October, in the year of our LORD, one thousand seven hundred and eighty-two, and of our Sovereignty and Independence, the seventh.

JOHN HANSON, President.

CHARLES THOMSON, Secretary.[45]

On Thursday, September 24, 1789, the first House of Representatives voted to recommend the First Amendment of the newly drafted Constitution to the states for ratification. The next day, Congressman Elias Boudinot from New Jersey proposed that the House and Senate jointly request of President Washington to proclaim a day of thanksgiving for "the many signal favors of Almighty God". Boudinot said he "could not think of letting the session pass over without offering an opportunity to all the citizens of the United States of joining, with one voice, in returning to Almighty God their sincere thanks for the many blessings he had poured down upon them."[47]

As President, on October 3, 1789, George Washington made the following proclamation and created the first Thanksgiving Day designated by the national government of the United States of America:

Whereas it is the duty of all Nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey his will, to be grateful for his benefits, and humbly to implore his protection and favor, and whereas both Houses of Congress have by their joint Committee requested me "to recommend to the People of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many signal favors of Almighty God especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a form of government for their safety and happiness."

Now therefore I do recommend and assign Thursday the 26th day of November next to be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being, who is the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be. That we may then all unite in rendering unto him our sincere and humble thanks, for his kind care and protection of the People of this Country previous to their becoming a Nation, for the signal and manifold mercies, and the favorable interpositions of his providence, which we experienced in the course and conclusion of the late war, for the great degree of tranquility, union, and plenty, which we have since enjoyed, for the peaceable and rational manner, in which we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness, and particularly the national One now lately instituted, for the civil and religious liberty with which we are blessed; and the means we have of acquiring and diffusing useful knowledge; and in general for all the great and various favors which he hath been pleased to confer upon us.

And also that we may then unite in most humbly offering our prayers and supplications to the great Lord and Ruler of Nations and beseech him to pardon our national and other transgressions, to enable us all, whether in public or private stations, to perform our several and relative duties properly and punctually, to render our national government a blessing to all the people, by constantly being a Government of wise, just, and constitutional laws, discreetly and faithfully executed and obeyed, to protect and guide all Sovereigns and Nations (especially such as have shown kindness unto us) and to bless them with good government, peace, and concord. To promote the knowledge and practice of true religion and virtue, and the increase of science among them and Us, and generally to grant unto all Mankind such a degree of temporal prosperity as he alone knows to be best.

Given under my hand at the City of New York the third day of October in the year of our Lord 1789.[48]

On January 1, 1795, Washington proclaimed a Thanksgiving Day to be observed on Thursday, February 19.

President John Adams declared Thanksgivings in 1798 and 1799.

As Thomas Jefferson was a deist and a skeptic of the idea of divine intervention, he did not declare any thanksgiving days during his presidency. His views on the matter of religious proclamations of the state were outlined in his 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptist Association:

Believing (...) that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, & not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should "make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof," thus building a wall of separation between Church & State. Adhering to this expression of the supreme will of the nation in behalf of the rights of conscience, I shall see with sincere satisfaction the progress of those sentiments which tend to restore to man all his natural rights, convinced he has no natural right in opposition to his social duties.[49][50]

James Madison renewed the tradition in 1814, in response to resolutions of Congress, at the close of the War of 1812. Caleb Strong, Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, declared the holiday in 1813, "for a day of public thanksgiving and prayer" for Thursday, November 25 of that year.[51]

Madison also declared the holiday twice in 1815; however, neither of these was celebrated in autumn. In 1816, Governor Plumer of New Hampshire appointed Thursday, November 14 to be observed as a day of Public Thanksgiving and Governor Brooks of Massachusetts appointed Thursday, November 28 to be "observed throughout that State as a day of Thanksgiving".[52]

A thanksgiving day was annually appointed by the governor of New York, De Witt Clinton, in 1817. In 1830, the New York State Legislature officially sanctioned Thanksgiving as a holiday, making New York the first state outside of New England to do so.[53][54]

Lincoln and the Civil War

In the middle of the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln, prompted by a series of editorials written by Sarah Josepha Hale,[55] began the regular practice of proclaiming a national Thanksgiving. His first proclamation, in April 1862 after the Union victories at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, the fall of Nashville, and another victory at Shiloh, recommended that Americans give thanks for these victories "at their next weekly assemblages."[56] It was the first federal Thanksgiving declaration since Madison's in 1815.[57] The next year, after victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Lincoln proclaimed a national Thanksgiving Day, to be celebrated on the 26th, the final Thursday of November 1863. The document, written by Secretary of State William H. Seward, reads as follows:

The year that is drawing towards its close has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added, which are of so extraordinary nature, that they cannot fail to penetrate and soften even the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever-watchful providence of Almighty God. In the midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity, which has sometimes seemed to foreign States to invite and to provoke their aggression, peace has been preserved with all nations, the order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed everywhere except in the theatre of military conflict; while that theatre has been greatly contracted by the advancing armies and navies of the Union. Needful diversions of wealth and of strength from the fields of peaceful industry to the national defense have not arrested the plow, the shuttle, or the ship; the ax had enlarged the borders of our settlements, and the mines, as well of iron and coal as of the precious metals, have yielded even more abundantly than heretofore. The population has steadily increased, notwithstanding the waste that has been made in the camp, the siege, and the battle-field; and the country, rejoicing in the consciousness of augmented strength and vigor, is permitted to expect continuance of years, with large increase of freedom.

No human counsel hath devised nor hath any mortal hand worked out these great things. They are the gracious gifts of the Highest God, who, while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy.

It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and voice by the whole American people. I do therefore invite my fellow-citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens. And I recommend to them that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to his tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility and Union.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand, and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the city of Washington, this third day of October, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and of the independence of the United States the eighty-eighth.

Proclamation of President Abraham Lincoln, October 3, 1863.[55][58]

Lincoln issued another proclamation of thanksgiving in October 1864, again for the last Thursday in November, after Union victories that included the fall of Atlanta and the capture of Mobile Bay.[59]

Post-Civil War era

Presidents continued to issue Thanksgiving proclamations on an annual basis, usually for the same time of year,[57] although in 1865 Andrew Johnson picked the first Thursday in December.[60]

On June 28, 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant signed into law the Holidays Act that made Thanksgiving a yearly "appointed or remembered" federal holiday in Washington D.C. Three other holidays included in the law were New Year, Christmas, and July 4. The law did not extend outside of Washington D.C., while the date assigned for Thanksgiving was left to the discretion of the President.[61][62][63] In January 1879, George Washington's Birthday, February 22, was added by Congress to the federal holidays list.[64] On January 6, 1885, a Congressional act expanded the Holidays Act to apply to all federal departments and employees throughout the nation. Federal workers received pay for all the holidays, including Thanksgiving.[64]

During the second half of the 19th century, Thanksgiving traditions in America varied from region to region. A traditional New England Thanksgiving, for example, consisted of a raffle held on Thanksgiving Eve (in which the prizes were mainly geese or turkeys), a shooting match on Thanksgiving morning (in which turkeys and chickens were used as targets), church services – and then the traditional feast, which consisted of some familiar Thanksgiving staples such as turkey and pumpkin pie, and some not-so-familiar dishes such as pigeon pie.[citation needed]

In New York City, people would dress up in fanciful masks and costumes and roam the streets in merry-making mobs. By the beginning of the 20th century, these mobs had morphed[citation needed] into Ragamuffin parades consisting mostly of children dressed as "ragamuffins" in costumes of old and mismatched adult clothes and with deliberately smudged faces, but by the late 1950s the tradition had diminished enough to only exist in its original form in a few communities around New York, with many of its traditions subsumed into the Halloween custom of trick-or-treating.[65]

Franksgiving (1939–1941)

Abraham Lincoln's successors as president followed his example of annually declaring the final Thursday in November to be Thanksgiving. But in 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt broke with this tradition.[66] November had five Thursdays that year (instead of the more-common four), Roosevelt declared the fourth Thursday as Thanksgiving rather than the fifth one. Although many popular histories state otherwise, he made clear that his plan was to establish the holiday on the next-to-last Thursday in the month instead of the last one. With the country still in the midst of The Great Depression, Roosevelt thought an earlier Thanksgiving would give merchants a longer period to sell goods before Christmas. Increasing profits and spending during this period, Roosevelt hoped, would help bring the country out of the Depression. At the time, advertising goods for Christmas before Thanksgiving was considered inappropriate. Fred Lazarus, Jr., founder of the Federated Department Stores, is credited with convincing Roosevelt to push Thanksgiving to a week earlier to expand the shopping season, and within two years the change passed through Congress into law.[67][68]

Republicans decried the change, calling it an affront to the memory of Lincoln. People began referring to November 30 as the "Republican Thanksgiving" and November 23 as the "Democratic Thanksgiving" or "Franksgiving".[69]

1942 to present

On October 6, 1941, both houses of the United States Congress passed a joint resolution fixing the traditional last-Thursday date for the holiday beginning in 1942. However, in December of that year the Senate passed an amendment to the resolution that split the difference by requiring that Thanksgiving be observed annually on the fourth Thursday of November, in order to prevent confusion on the occasional years in which November has five Thursdays.[70][62] The amendment also passed the House, and on December 26, 1941, President Roosevelt signed this bill, for the first time making the date of Thanksgiving a matter of federal law and fixing the day as the fourth Thursday of November.[71]

Traditional celebrations and solemnities

Foods of the season

Turkey, usually roasted and stuffed (but sometimes deep-fried instead), is typically the featured item on most Thanksgiving feast tables. 40 million turkeys were consumed on Thanksgiving Day alone in 2019.[72] With 85 percent of Americans partaking in the meal, an estimated 276 million Americans dine on the festive poultry, spending an expected $983.3 million on turkeys for Thanksgiving in 2024.[73][74]

Mashed potatoes with gravy, stuffing, sweet potatoes, cranberry sauce, sweet corn, various fall vegetables, squash, and pumpkin pie are among the side dishes commonly associated with Thanksgiving dinner.[75]

Giving thanks and religious activity

The tradition of giving thanks is continued today in many forms, most notably the attendance of religious services, as well as the saying of a mealtime prayer before Thanksgiving dinner.[5]

At home, it is a holiday tradition in many families to begin the Thanksgiving dinner by saying grace (a prayer before or after a meal).[76] Before praying, it is a common practice at the dining table for "each person [to] tell one specific reason they're thankful to God that year".[77][78][79]

Joy Fisher, a Baptist writer, states that "this holiday takes on a spiritual emphasis and includes recognition of the source of the blessings they enjoy year round – a loving God."[80] In the same vein, Hesham A. Hassaballa, an American Muslim scholar and physician, has written that Thanksgiving "is wholly consistent with Islamic principles" and that "few things are more Islamic than thanking God for His blessings".[81] Similarly many Sikh Americans also celebrate the holiday by "giving thanks to Almighty".

Many houses of worship offer worship services and events on Thanksgiving themes the weekend before, the day of, or the weekend after Thanksgiving.[82] Thanksgiving is included in the Revised Common Lectionary, which provides scriptures for Thanksgiving services. It is the last entry on the liturgical calendar before the start of Advent the following Sunday.[83]

Charity

The poor are often provided with food at Thanksgiving time. Most communities have annual food drives that collect non-perishable packaged and canned foods, and corporations sponsor charitable distributions of staple foods and Thanksgiving dinners.[84] The Salvation Army enlists volunteers to serve Thanksgiving dinners to hundreds of people in different locales;[85][86] the Salvation Army also uses Thanksgiving as the day it launches its annual kettle campaign, with the launch coinciding with a nationally televised concert.[87] The United Way also launches its Live United campaign on Thanksgiving.[88][89]) Additionally, five days after Thanksgiving is Giving Tuesday, a celebration of charitable giving.[90]

Parades

Since 1924, in New York City, the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade is held annually every Thanksgiving Day from the Upper West Side of Manhattan to Macy's flagship store in Herald Square, and televised nationally by NBC. The parade features parade floats with specific themes, performances from Broadway musicals, large balloons of cartoon characters, TV personalities, and high school marching bands. The float that traditionally ends the Macy's Parade is the Santa Claus float, the arrival of which is an unofficial sign of the beginning of the Christmas shopping season. It is billed as the world's largest parade.[91]

The oldest Thanksgiving Day parade is Philadelphia's Thanksgiving Day Parade, which launched in 1920. Philadelphia's parade was long associated with Gimbels, a prominent Macy's rival, until that store closed in 1986.[92]

Founded in 1924, the same year as the Macy's parade, America's Thanksgiving Parade in Detroit is one of the largest parades in the country.[93] The parade runs from Midtown to Downtown Detroit and precedes the annual Detroit Lions Thanksgiving football game.[94] The parade includes large balloons, marching bands, and various celebrity guests much like the Macy's parade and is nationally televised on various affiliate stations.[95] The Mayor of Detroit closes the parade by giving Santa Claus a key to the city.[95]

There are Thanksgiving parades in many other cities, including:

- Ameren Missouri Thanksgiving Day Parade[96] (St. Louis, Missouri)

- America's Hometown Thanksgiving Parade (Plymouth, Massachusetts)

- Belk Carolinas' Carrousel Parade (Charlotte, North Carolina)

- Celebrate the Season Parade (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania)

- FirstLight Federal Credit Union Sun Bowl Parade[97] (El Paso, Texas)

- H-E-B Holiday Parade[98] (Houston, Texas)

- Chicago Thanksgiving Parade (Chicago, Illinois)

- Santa Claus Parade (Peoria, Illinois), the nation's oldest, dating to 1887 and held the day after Thanksgiving[99]

- Parada de los Cerros Thanksgiving Day Parade[100] (Fountain Hills, Arizona)

- UBS Parade Spectacular[101] (Stamford, Connecticut) – held the Sunday before Thanksgiving so it does not directly compete with the Macy's parade 30 miles (48 km) away.

Most of these parades are televised on a local station, and some have small, usually regional, syndication networks; most also carry the parades via Internet television on the TV stations' websites.

Several other parades have a loose association with Thanksgiving, thanks to CBS's now-discontinued All-American Thanksgiving Day Parade coverage. Parades that were covered during this era were the Aloha Floral Parade held in Honolulu, Hawaii every September,[102] the Toronto Santa Claus Parade in Toronto, Ontario, Canada,[103] and the Opryland Aqua Parade (held from 1996 to 2001 by the Gaylord Opryland Resort & Convention Center in Nashville);[104] the Opryland parade was discontinued and replaced by a taped parade in Miami Beach, Florida in 2002.

For many years the Santa Claus Lane Parade (now Hollywood Christmas Parade) in Los Angeles was held on the Wednesday evening before Thanksgiving. In 1978 this was switched to the Sunday following the holiday.[105]

Sports

American football

American football is an important part of many Thanksgiving celebrations in the United States, a tradition that dates to the earliest era of the sport in the late 19th century.[106] Professional football games are often held on Thanksgiving Day; until 2005, these were the only regular season games that the National Football League played during the week apart from Sunday or (from 1970 onward) Monday nights. The NFL has played games on Thanksgiving every year since its creation except during World War II, a series formally known as the John Madden Thanksgiving Celebration since 2022. The Detroit Lions hosted a game every Thanksgiving Day from 1934 to 1938 and have hosted one every year since 1945.[107] In 1966, the Dallas Cowboys, which were founded six years earlier, adopted the practice of hosting Thanksgiving games.[108] The league added a third game in prime time in 2006; unlike the traditional afternoon doubleheader, this game has no fixed host.[109]

For college football teams that participate in the highest level (all teams in the Football Bowl Subdivision, as well as three teams in the historically black Southwestern Athletic Conference of the Championship Subdivision), the regular season ends on Thanksgiving weekend, and a team's final game is often against a regional or historic rival, such as the Iron Bowl between Alabama and Auburn, the rivalry formerly known as the Oregon Civil War between Oregon and Oregon State, the Apple Cup between Washington and Washington State, and Michigan and Ohio State playing in their rivalry game.[110]

Some high school football games (which include some state championship games), and informal "Turkey Bowl" contests played by amateur groups and organizations, are frequently held on Thanksgiving weekend.[111] High school contests were once commonplace on the holiday but have rapidly declined since the late 20th century and into the early 21st century (except in portions of New England, New Jersey and widely scattered examples elsewhere) as schools shift their focus to state tournaments and winter sports.[112][113] Games of football preceding or following the meal in the backyard or a nearby field are also common during many family gatherings. Amateur games typically follow less organized backyard-rules, two-hand touch or flag football styles.[114]

Other sports

College basketball holds several elimination tournaments on over Thanksgiving weekend, before the conference season. These include the Vegas Showdown,[115] the Orlando-based ESPN Events Invitational,[116] the Maui Invitational, and the Bahamas-based Battle 4 Atlantis,[117] all of which are televised on ESPN2 and ESPNU in marathon format, while TNT Sports carries the Players Era Festival.[118] The NCAA owned-and-operated NIT Season Tip-Off has also since moved to Thanksgiving week.[119]

Though golf and auto racing are in their off-seasons on Thanksgiving, there are events in those sports that take place on Thanksgiving weekend. The Turkey Night Grand Prix is an annual automobile race that takes place at various venues in southern California on Thanksgiving night;[120] due in part to the fact that this is after the NASCAR Cup Series and IndyCar Series have finished their seasons, it allows some of the top racers in the United States to participate. In golf, Thanksgiving weekend was the traditional time of the Skins Game from 1983 to 2008,[121] with the event being abandoned during the late 2000s recession and revived as a streaming-only event in 2025.[122] During that 17-year hiatus, the concept of a special golf event on Thanksgiving weekend was revived in the form of The Match, a sports entertainment tournament held most years on or near Thanksgiving from 2018 to 2024.[123]

The world championship pumpkin chunking contest was held in early November in Delaware and televised each Thanksgiving on Science Channel, but the event was mired in liability disputes following injuries at the events in the 2010s; it has been held only once since 2016,[124] a 2019 contest in Illinois that had far fewer competitors and ran a financial loss.[125]

In ice hockey, the National Hockey League announced, as part of its decade-long extension with NBC, that they would begin airing a game on the Friday afternoon following Thanksgiving beginning the 2011–12 NHL season; the game has since been branded as the "Thanksgiving Showdown". (The Boston Bruins have played matinees on Black Friday since at least 1990, but 2011 was the first time the game was nationally televised.)[126]

Professional wrestling promotions have typically held premier pay-per-view events on or around the time of Thanksgiving. This trend began in 1983 when Jim Crockett Promotions, the largest promoter in the National Wrestling Alliance, introduced Starrcade. Starrcade, later incorporated into World Championship Wrestling, moved off Thanksgiving in 1988;[127] the year prior, the rival World Wrestling Federation had introduced Survivor Series, an event that continues to be hosted in November to the present day.[128]

Many American cities hold road running events, known as "turkey trots", on Thanksgiving morning, so much so that as of 2018[update], Thanksgiving is the most popular race day in the U.S.[129] Depending on the organizations involved, these can range from one-mile (1.6 km) fun runs to full marathons (although no races currently use the latter; the Atlanta Marathon stopped running on Thanksgiving in 2010).[130] The oldest continually running annual footrace in North America, the YMCA Buffalo Niagara Turkey Trot, is among these races.[131]

In soccer, Major League Soccer announced in 2021 that a MLS Cup Playoffs match will be held on Thanksgiving for the first time, with a Conference Semifinals match of the 2021 Playoffs between the Colorado Rapids and the Portland Timbers held on that day. While the MLS Cup playoffs were usually held from October to December, no MLS match was held on a Thanksgiving Day before 2021.[132] The experiment was not reprised after 2021 as MLS Cup Playoff games have been scheduled solely for Saturdays and Sundays since then.

Television

While not as prolific as Christmas specials, which usually begin right after Thanksgiving, there are many special television programs transmitted on or around Thanksgiving, such as A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving, in addition to the live parades and football games mentioned above. In some cases, television broadcasters begin programming Christmas films and specials to run on Thanksgiving Day, taking the day as a signal for the beginning of the Christmas season.[citation needed]

Radio

"Alice's Restaurant", an 18-minute monologue by Arlo Guthrie which is partially based on an incident that happened on Thanksgiving in 1965, was first released in 1967. It has since become a tradition on numerous classic rock and classic hits radio stations to play the full, uninterrupted recording to much fanfare each Thanksgiving Day, a tradition that appears to have originated with counterculture radio host Bob Fass, who introduced the song to the public on his radio show.[133] Another song that traditionally gets played on numerous radio stations (of many different formats) is "The Thanksgiving Song", a 1992 song by Adam Sandler.[134] "Grandma's Thanksgiving," a 1947 suite that occupies both sides of a 78 RPM album by Fred Waring, is a recurring tradition on WBEN in Buffalo, New York, where it was a longstanding tradition of morning host Clint Buehlman and has continued under succeeding hosts Bill Lacy and Randy Bushover.[135][136]

In the beginning of the 21st century, Thanksgiving or the day after was the traditional start date when radio stations flipped to continuous Christmas music. Due to Christmas creep, this date has progressed to well before Thanksgiving for most stations that follow this strategy.[137]

Historically, The Rush Limbaugh Show carried a tradition of "The True Story of Thanksgiving," a monologue in which host Rush Limbaugh, reciting from his book See, I Told You So, highlighted lesser-known aspects of the traditional Plymouth story, with particular emphasis on the ill-fated decision to pool all of the colony's resources commonly, which he used as a cautionary tale against modern-day socialism.[138] All Things Considered host Susan Stamberg traditionally shared her mother-in-law's recipe for cranberry relish, which included uncharacteristic savory and spicy ingredients including onion and horseradish, each Thanksgiving.[139]

Turkey pardoning

The President of the United States has received a Thanksgiving turkey every year since 1873; for the first 41 years, the turkey was provided by Westerly, Rhode Island turkey kingpin Horace Vose. In 1947, in what began as a lobbying ploy to get President Harry S. Truman to stop rationing turkey for foreign aid, the National Turkey Federation has presented the President of the United States with one live turkey and two dressed turkeys in a ceremony known as the National Thanksgiving Turkey Presentation. John F. Kennedy was the first president reported to spare the turkey given to him (he said he did not plan to eat the bird); by the late 1970s, most of the turkeys were being sent to petting zoos, while the dressed turkeys are usually sent to a charity such as Martha's Table.[140]

Some legends date the origins of pardoning turkey to the Truman administration or even to Abraham Lincoln pardoning his son's Christmas turkey;[141] both stories have been quoted in more recent presidential speeches, but neither has any evidence in the Presidential record.[142]

In more recent years, two turkeys have been pardoned, in case the original turkey becomes unavailable for presidential pardoning.[143][144]

George H. W. Bush made the turkey pardon a permanent annual tradition upon assuming the presidency in 1989, a tradition that was possibly inspired in part by a joke his predecessor Ronald Reagan had cracked during the 1987 presentation and has been carried on by every president each year since.[145][146] After stints at Frying Pan Farm Park in Herndon, Virginia (1989 to 2004),[147] the Disney Resorts (2005 to 2009),[146] Mount Vernon (the estate of George Washington, 2010 to 2012), and Morven Park (the estate of Westmoreland Davis, 2013 to 2015), turkeys have lived the remainder of their lives in the care of agricultural departments of major universities. The turkeys rarely lived to see the next Thanksgiving due to being bred for large size;[141] this gradually improved over the course of the 2010s as Morven Park and the universities have been more aggressive in maintaining the turkeys' health.[148]

Vacation and travel

On Thanksgiving Day, families and friends usually gather for a large meal or dinner.[149] Consequently, the Thanksgiving holiday weekend is one of the busiest travel periods of the year.[150] Thanksgiving is a four-day or five-day weekend vacation for schools and colleges. Most business and government workers (78% as of 2007) are given Thanksgiving and the day after as paid holidays.[151] Thanksgiving Eve (also known as Blackout Wednesday), the night before Thanksgiving, is one of the busiest nights of the year for bars and clubs as many college students and others return to their hometowns to reunite with friends and family.[152]

Criticism, controversy and alternative observations

Due to the popularity of the Thanksgiving festivities in the U.S., the holiday has attracted protests and alternative observation traditions.

Indigenous protests

Much like Columbus Day, Thanksgiving has been subject to criticism under the lens of tribal critical race theory. It is observed by some Native Americans as a "National Day of Mourning", in acknowledgment of the Native American genocide in the United States.[153][154][155] Thanksgiving has long carried a distinct resonance for many Native Americans, who see the holiday as an embellished story of "Pilgrims and Natives looking past their differences" to break bread.[156] Some Native Americans hold "Unthanksgiving Day" celebrations in which they mourn the deaths of their ancestors, fast, dance, and pray.[157] This tradition has been taking place since 1975.[158] Since 1970, the United American Indians of New England, a protest group led by Frank "Wamsutta" James (Aquinnah Wampanoag, 1923−2001), has accused the United States of fabricating the Thanksgiving story and of whitewashing genocide and injustice against Native Americans, and it has led a National Day of Mourning protest on Thanksgiving at Plymouth Rock in Plymouth, Massachusetts in the name of social equality and political prisoners.[159][160]

Professor David J. Silverman notes that the story of the pilgrims and their Wampanoag allies dining together in peace mythologized this interaction while the later breakdown in relations between the two groups was ignored. He believes that this perpetuates the notion that the Wampanoag's chief legacy was to present America as a gift to the pilgrims and to concede to colonialism similar to the stories of Pocahontes and Sacagawea.[29] Professor R. W. Jensen of the University of Texas at Austin writes that "One indication of moral progress in the United States would be the replacement of Thanksgiving Day and its self-indulgent family feasting with a National Day of Atonement accompanied by a self-reflective collective fasting."[161]

The autobiography of Mark Twain, first published in 1924, gives the satirical opinion of Mark Twain thus:[162]

Thanksgiving Day, a function which originated in New England two or three centuries ago when those people recognized that they really had something to be thankful for – annually, not oftener – if they had succeeded in exterminating their neighbors, the Indians, during the previous twelve months, instead of getting exterminated by their neighbors, the Indians. Thanksgiving Day became a habit, for the reason that in the course of time, as the years drifted on, it was perceived that the exterminating had ceased to be mutual and was all on the white man's side, consequently on the Lord's side; hence it was proper to thank the Lord for it and extend the usual compliments.

Those who view Thanksgiving negatively generally acknowledge their perspective as a small minority view; author and humanist J. G. Rodwan, who does not celebrate Thanksgiving, noted that those who attempt to tie Thanksgiving to colonialism and genocides "are likely to be dismissed as some sort of crank".[163] A Vancouver Sun story covering native views of the holiday in the United States and Canada noted that the disapproving position "by no means represents all the (United States') indigenous people" and that such ideas were rare in rural areas where native reservations were typically established, and more commonly seen in urban areas of the United States and in academia.[164] Frank James's granddaughter Kisha acknowledged in 2020 that her grandfather's hostilities had no precedent or attestation prior to 1970.[165]

Native American harvest festivals and Thanksgiving traditions

The perception of Thanksgiving among Native Americans is not, however, universally negative and some do celebrate the holiday. Tim Giago (Oglala Lakota, 1934–2022), founder of the Native American Journalists Association, sought to reconcile Thanksgiving with Native American fall harvest celebrations. He compares Thanksgiving to "wopila", a thanks-giving celebration practiced by Native Americans of the Great Plains. He wrote in The Huffington Post: "The idea of a day of Thanksgiving has been a part of the Native American landscape for centuries. The fact that it is also a national holiday for all Americans blends in perfectly with Native American traditions." He also shares personal anecdotes of Native American families coming together to celebrate Thanksgiving.[166]

Oneida participation in commercial Thanksgiving parade

Members of the Oneida Indian Nation marched in the 2010 Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade with a float called "The True Spirit of Thanksgiving" and have done so every year since.[167]

Blamesgiving

In the early part of the 20th century, the American Association for the Advancement of Atheism (4A) opposed the celebration of Thanksgiving Day, offering an alternative observance called Blamegiving Day, which was in their eyes, "a protest against Divine negligence, to be observed each year on Thanksgiving Day, on the assumption, for the day only, that God exists".[168] Citing their view of the separation of church and state, some atheists have particularly criticized the annual recitation of Thanksgiving proclamations by the President of the United States in recent times, because these proclamations often revolve around the theme of giving thanks to God.[169]

Retail workers' rights

The move by retailers to begin holiday sales during Thanksgiving Day (as opposed to the traditional day after) has been criticized as forcing (under threat of being fired) low-end retail workers, who compose an increasing share of the nation's workforce, to work odd hours and to handle atypical, unruly crowds on a day reserved for rest.[170]

In response to this controversy, Macy's and Best Buy (both of which planned to open on Thanksgiving, even earlier than they had the year before) stated in 2014 that most of their Thanksgiving Day shifts were filled voluntarily by employees who would rather have the day after Thanksgiving off instead of Thanksgiving itself.[171][172] This practice has become common (but not universal) as of 2024.

By 2021, retailers had largely abandoned efforts to hold Thanksgiving doorbusters and returned their focus to Black Friday proper.[173] Blue laws in several Northeastern states[which?] prevent retailers in those states from opening on Thanksgiving. Such retailers typically opened at midnight on the day after Thanksgiving.[172]

Harvest of Shame

Journalist Edward R. Murrow and producer David Lowe deliberately chose the Thanksgiving weekend of 1960 as the date when they broadcast Murrow's final story for CBS News. Entitled Harvest of Shame, the hour-long documentary was designed "to shock Americans into action" regarding the treatment of impoverished migrant farmworkers in the country, hoping to contrast the Thanksgiving dinner and the excesses of it with the poverty of those who picked the vegetables.[174] Murrow acknowledged the fact that the documentary was hostile toward the United States because it portrayed the United States in a negative light, and when he left CBS to join the United States Information Agency in 1961, he unsuccessfully attempted to stop the special from being broadcast in the United Kingdom.[175][176]

Vegetarian Thanksgiving

Vegetarians have criticized the holiday and its focus on the consumption of turkeys since before the holiday was officially recognized in the U.S. In the nineteenth century, American vegetarians created a distinct Thanksgiving menu. Nineteenth-century newspaper editor and vegetarian Jeremiah Hacker criticized the holiday in 1848 and 1859. The first recipe for a vegetarian turkey was published in the U.S. in 1891.[177] In 1894, Ella Eaton Kellogg published a recipe for vegetarian mock turkey.[178] One of the earliest known vegetarian Thanksgiving dinners was held in 1895 at the University of Chicago.[179] During the twentieth century, many recipes for vegetarian turkey were published.[180][181] The Millennium Guild in Boston held a vegetarian Thanksgiving at the Copley Hotel in 1913 where a Golden Rule Roast was served.[177][179] In 1995, Tofurky was first sold commercially.[178]

Date

Since being fixed on the fourth Thursday in November by law in 1941 (from 1863 to 1940 it was on the last Thursday in November),[71] the holiday in the United States can occur on any date from November 22 to 28 (November 24 to 30 from 1863 to 1940). When it falls on November 22 or 23, it is not the last Thursday, but the penultimate Thursday in November. Regardless, it is the Thursday preceding the last Saturday of November.

Because Thanksgiving is a federal holiday, all United States government offices are closed and all employees are paid for that day. It is also a holiday for the New York Stock Exchange and most other financial markets and financial services companies.[182]

Table of dates (1863–2103)

The date of Thanksgiving Day follows a 28-year cycle, broken only by century years that are not a multiple of 400 (e.g. 1900, 2100, 2200, 2300, 2500 ...). The break in the regular cycle is an effect of the leap year algorithm, which dictates that such years are common years as an adjustment for the calendar / season alignment that leap years provide. Past and future dates of celebration include:[183]

| November 22 | November 23 | November 24 | November 25 | November 26 | November 27 | November 28 | November 29 | November 30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Possible | 1864 | 1863 | Dates not possible due to Thanksgiving being on various days during these years (pre-1863) | |||||

| 1870 | 1869 | 1868 | 1867 | 1866 | 1865 | |||

| 1875 | 1874 | 1873 | 1872 | 1871 | ||||

| 1881 | 1880 | 1879 | 1878 | 1877 | 1876 | |||

| 1887 | 1886 | 1885 | 1884 | 1883 | 1882 | |||

| 1892 | 1891 | 1890 | 1899 | 1888 | ||||

| 1898 | 1897 | 1896 | 1895 | 1894 | 1893 | |||

| 1904 | 1903 | 1902 | 1901 | 1900 | 1899 | |||

| 1910 | 1909 | 1908 | 1907 | 1906 | 1905 | |||

| 1915 | 1914 | 1913 | 1912 | 1911 | ||||

| 1921 | 1920 | 1919 | 1918 | 1917 | 1916 | |||

| 1927 | 1926 | 1925 | 1924 | 1923 | 1922 | |||

| 1932 | 1931 | 1930 | 1929 | 1928 | ||||

| 1938 | 1937 | 1936 | 1935 | 1934 | 1933 | |||

| 1945 | 1944 | 1943 | 1942 | 1941 | 1940 | 1939 | ||

| 1951 | 1950 | 1949 | 1948 | 1947 | 1946 | Not Possible | ||

| 1956 | 1955 | 1954 | 1953 | 1952 | ||||

| 1962 | 1961 | 1960 | 1959 | 1958 | 1957 | |||

| 1967 | 1966 | 1965 | 1964 | 1963 | ||||

| 1973 | 1972 | 1971 | 1970 | 1969 | 1968 | |||

| 1979 | 1978 | 1977 | 1976 | 1975 | 1974 | |||

| 1984 | 1983 | 1982 | 1981 | 1980 | ||||

| 1990 | 1989 | 1988 | 1987 | 1986 | 1985 | |||

| 1995 | 1994 | 1993 | 1992 | 1991 | ||||

| 2001 | 2000[i] | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | 1996 | |||

| 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | |||

| 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | ||||

| 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | |||

| 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | ||||

| 2029 | 2028 | 2027 | 2026 | 2025 | 2024 | |||

| 2035 | 2034 | 2033 | 2032 | 2031 | 2030 | |||

| 2040 | 2039 | 2038 | 2037 | 2036 | ||||

| 2046 | 2045 | 2044 | 2043 | 2042 | 2041 | |||

| 2051 | 2050 | 2049 | 2048 | 2047 | ||||

| 2057 | 2056 | 2055 | 2054 | 2053 | 2052 | |||

| 2063 | 2062 | 2061 | 2060 | 2059 | 2058 | |||

| 2068 | 2067 | 2066 | 2065 | 2064 | ||||

| 2074 | 2073 | 2072 | 2071 | 2070 | 2069 | |||

| 2079 | 2078 | 2077 | 2076 | 2075 | ||||

| 2085 | 2084 | 2083 | 2082 | 2081 | 2080 | |||

| 2091 | 2090 | 2089 | 2088 | 2087 | 2086 | |||

| 2096 | 2095 | 2094 | 2093 | 2092 | ||||

| 2103 | 2102 | 2101 | 2100 | 2099 | 2098 | 2097 | ||

- ^ In most century years, the week / date pattern would break, but since 2000 was a 400 year century-year, the century-year exception does not apply.

Days after Thanksgiving